Have you read “How to Get Rid of Stuff: The Survey Says…”?

Published on Next Avenue, the article features an interview with David J. Ekerdt, author of Downsizing: Confronting Our Possessions in Later Life.

Although I’m too busy confronting my own mountain of stuff to read Ekerdt’s book, the article brought me face-to-face with my own struggle to take control of my possessions.

One line in particular stood out to me. It referred to the “magical thinking” approach to downsizing, which can be summed up as wishing a fire would “take care of” all one’s possessions.

I’ve been guilty of such thinking. In fact, more than a decade ago, I fantasized about this exact thing with my friend Maery Rose.

Last week my fantasy almost came true.

That’s when I came home from a socially distanced visit with my aunt Caroline to a smoke-filled bedroom.

It started because of my hair.

I haven’t had it cut or colored since the pandemic began, and it’s been driving me crazy. I wanted to give it a bit of TLC from all angles, so I plugged in a curling iron in my bedroom, where I could adjust the mirrored bifold doors of my closet to get a 360-degree view of my hair.

Though I didn’t love what I saw, a figured a few quick curls just before walking out the door would get me to “good enough.”

But in the middle of making those curls, I got distracted by a call and forgot to turn the curling iron off. What’s worse, while I was gone, it slipped from the radiator onto my bed, where I had a pile of clothes I’d been debating about whether to keep or giveaway.

By the time I returned home, the curling iron had burned through the clothes, as well as a treasured handmade afghan, my down comforter and my sheets. Even my mattress was beginning to burn.

I’m lucky I came home when I did. The damage could have been much worse. And while I certainly hope I never accidentally set another thing on fire, there’s one positive that came out of that day: I’m finally, after years of talking about doing so, letting go of those things that don’t fit my future self.

In fact, in the week since the fire, I’ve donated two carloads of boxes and filled my dining room with dozens more.

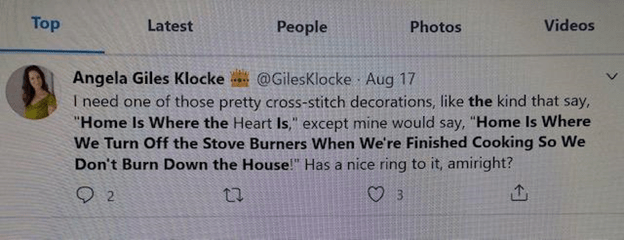

And thanks to this tweet by Angela Giles Klocke, I’m able to see some humor in the fact that the universe had to light a fire in my bed in order for me to finally take downsizing seriously.

Inspired by Angela, I’m now cross-stitching my own aphorism: “Home Is Where We Unplug Curling Irons So We Don’t Burn Down the House!”

Angela is right, it does have a nice ring to it, one I hope will keep both my home and hers fire-free from now on.