It is somewhere else and happens to someone else, not in your hometown, not in your classroom, and not with your kids.

Missouri dad shoots at wife, kills their infant child. May 24, 2016

Father killed 3 children, wife, then himself in Pennsylvania home. August 15, 2016

Dad kills two children then himself in Beaverton, Oregon. October 5, 2016

The morning we got the news, I heard Jody talking on the phone downstairs. When she came up she handed me the Saturday paper.

Man, two teens dead after south Minneapolis domestic shooting.

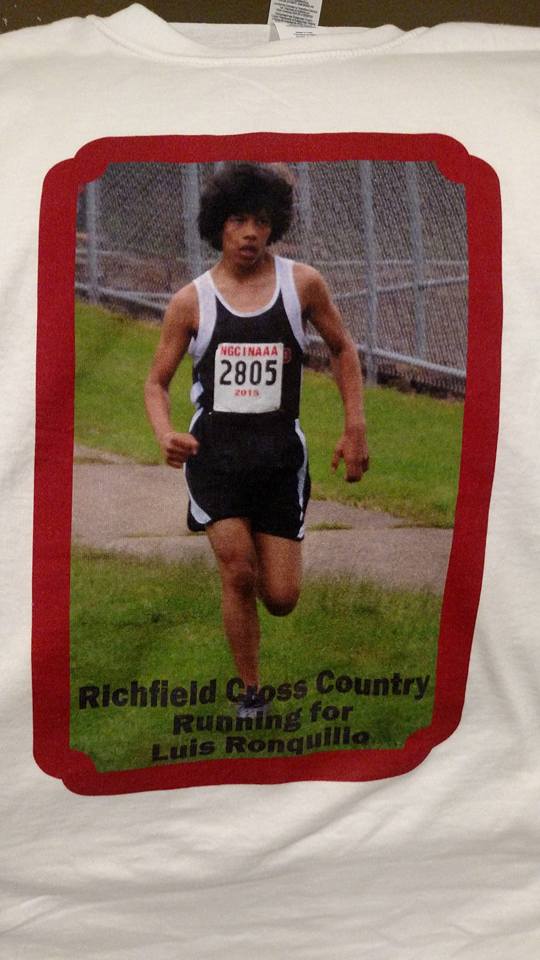

“This is Luis,” she said. “No, not Luis,” was my response. “Not our Luis.”

“This is Luis,” she said. “No, not Luis,” was my response. “Not our Luis.”

I immediately went to the last time I saw Luis. It was at our house this past summer. Luis’s birthday is a day before Juan’s. Through the years they have been to each other’s birthday party. This year, Juan’s party was on Luis’s actual birthday. A van load of teens sang “Happy Birthday” to Luis when we picked him up for paintball and again when we cut Juan’s birthday cake.

Each Happy Birthday elicited from Luis the tiniest of smiles. Luis didn’t smile much. I’d see him from time to time in Juan’s classes when I’d accompany Juan because I was trying to understand why he was tardy. I never did figure it out. But it would be old home week for me when I’d see Luis and the other students that I knew from being a school volunteer.

On one of my ‘why are you tardy’ class visits, his friend Oliver asked me why I was there.

“It’s bring your mother to school day,” I told him. “Obviously, no one else got the memo,” I added, as I looked around the classroom.

Of course, I’d do what I could to embarrass Juan. I’d pull a chair up and sit right next to him, say hi and wave to his classmates.

During that class, I spent a lot of the time watching Luis. He was different. Quiet. Didn’t say anything. I mentioned this to Juan. “Luis never says a word.” He agreed. “Sometimes, Kevin can make him laugh,” he said.

When it came time to tell Juan about Luis, I knocked on his bedroom door. His room was a dark cave with only the glow from his iPhone. I flipped on the light switch, sat down and handed him the Saturday paper. “This is what’s called domestic violence. This is your friend, Luis.”

I’m no stranger to domestic violence. I grew up in a home that was violent. One particular afternoon, when I was Juan and Luis’s age, I had my hand on the phone in the kitchen. I was sure my dad would kill my mom or my mom would kill my dad. I couldn’t take my eyes off of them as they circled each other. Two of my older brothers were discussing amongst themselves how to break up the fight. I was debating whether I should call the cops from the house phone or run to the barn and use the barn phone so my parents wouldn’t know who called. I couldn’t pull myself away. I was afraid of what would happen if I did.

In parenting Juan and Crystel, I’ve been adamant that our house be a safe zone. Negative talk or actions are not tolerated. Jody and I’ve extended this safety to their friends. “Tell them where our housekey is. Let them know they can come here if they need a place to come.”

What I didn’t realize then is that Jody and I were creating a safe haven for me. I’m able to finally rest. I fall asleep. I snore. I’m not always on alert. I’m not afraid anymore.

Soon after Crystel learned that Luis had died from domestic violence she asked me if I ever got mad at her. I paused, “Mad enough to shoot you in the head?”

She hesitated, “Well, yeah.”

I told her, “No, I never get that mad. I don’t even get mad enough to hit you. You irritate me sometimes. But, mostly I just like being around you and Juan.”

I knew the conversation was over when she took it to where she usually takes a conversation, “Do I irritate you more or does Juan?”

Later that day, I realized that I had forgotten to tell her something so I brought it up the next day. “Luis didn’t do anything wrong. His dad wasn’t mad at him. Luis is dead because his dad was mad at his mom. Not because of anything he did.”

In talking with Veronica Bach Dowd, a very close friend of Luis and Nahily’s mom, Maria Romero, she spoke about how difficult it is for Latino women to report abuse. Veronica previously worked at Casa de Esperanza as an advocate for battered women.

She explained that in Mexico, domestic violence is common. For a Latino woman in a new country it’s even worse because of the isolation. Women are isolated because of language barriers, not knowing about resources, and not having any money. The abuser “takes care” of the woman by driving her everywhere to not allow her to get a driver’s license. The abuser “takes care” of the woman by paying for everything to not allow her to be independent and self sufficient. She added, “Control is how abusers keep abused women invisible.”

A Latino woman may be afraid to report abuse due to the threat of being deported, or having their children taken away. The abuser and the children may have residency, but the woman might not. The Latino woman is stuck, remains invisible, and under the radar, so she uses makeup to hide the bruises and great excuses to avoid questions.

That’s why Veronica helped open a resource center for Latino women. It was a little office where any woman could go to ask any question. She would help them open Hotmail accounts so they could email people in their home town in Mexico.

Veronica has been friends with Maria for over nine years. She watched her grow from being in a cocoon, to a caterpillar, to a butterfly. Her eyes kept getting bigger and bigger. Veronica helped in Maria’s transformation by assisting her with filling out her first online application to become a paraprofessional at Richfield Dual Language School. Veronica watched Maria grow into a strong, self sufficient, beautiful free woman.

Veronica has been friends with Maria for over nine years. She watched her grow from being in a cocoon, to a caterpillar, to a butterfly. Her eyes kept getting bigger and bigger. Veronica helped in Maria’s transformation by assisting her with filling out her first online application to become a paraprofessional at Richfield Dual Language School. Veronica watched Maria grow into a strong, self sufficient, beautiful free woman.

Until it becomes personal it is somewhere else, some place else, somebody’s else’ kid. Luis, his sister Nahily, and mother Maria Romero, have made domestic violence personal for our house, for our school, and our community.

For families experiencing domestic violence, Casa de Esperanza and The Family Partnership offer Spanish- speaking resources.