Growing up, I recall elders recounting tales about life before some innovation. Today, the advent of artificial intelligence (AI) is a hinge moment like so many technological advances I’ve experienced in the last 40 years. I look back on past breakthroughs with wonder and nostalgia. I’m trying to come to terms with current developments.

1984 – Desktop Computers

I roll my eyes when young volunteer coordinators enquire if I’m comfortable with computers. In 1984, my boss handed me boxes for an Apple IIe desktop computer and an amber monitor (orange type on a black screen) and told me to set them up so I could write marketing and training materials.

1989 – Internet

Today, that old setup is quaint and humorous—a one-color monitor, 5¼ inch diskettes, a computer that didn’t connect to the Internet . . . because the World Wide Web wasn’t mainstream until 1989-90.

When the Internet became commonplace, we used painfully slow telephone dial-up modems with their crackling static and rubber band sound. Modems meant I no longer had to courier work product files to my customers on diskettes, which had shrunk to 3½ inches.

1994 – 2001 – Search Engines and Websites

In the mid-1990s, search engines like Yahoo, AOL, and Netscape came on the scene and Search Engine Optimization (SEO) helped people, products, and businesses get found. Google started in 1998. It’s hard to imagine a time before Google, when research meant visiting a brick and mortar library to use printed resources that might be checked out to someone else.

As websites grew common, having one for my business became important. A friend and I designed and rolled out mine in 2001. Several versions followed until I retired it several years ago.

1996 – Cell Phones

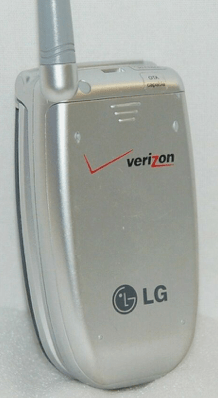

For me, the next technological cliff came around 1996 or 1997 when small cell phones arrived. They made calls. That’s it. If you had the patience to tap number buttons repeatedly, you could eke out texts. No camera. No Internet. No email. No music. No maps. Next, I owned a different dumb phone that opened to a qwerty keyboard. Around 2005, I acquired a fancier flip phone with a camera. Woohoo! Before long my 35mm digital camera was obsolete.

2007 – Smartphones

The world shifted dramatically again when the iPhone was introduced in 2007—the best of the available smartphones. Cell phones had enabled me to keep up on client calls and emails seamlessly when I was away from my home office—in other words, an early version of remote work. Staying connected with family became immensely simpler too.

2007 – 2008 – Facebook & Twitter

The advent of social media—Facebook and Twitter along with their many step-children—has transformed the world. How we discover, understand, and consume news. How we see ourselves and connect with or demonize others. There’s no denying social media’s far-reaching impact. Despite my mixed feelings about Facebook, it’s where a number of readers find our blogs.

Now – Artificial Intelligence

Evidence of artificial intelligence is everywhere—Siri and Alexa, helpful spelling prompts in texts and emails, blank-eyed, AI-drawn models in ads, and who knows how many AI functions we are unaware of.

AI makes me uneasy. But I don’t want to be a Luddite, so I’ve told myself I really ought to dig in, try to understand its scope, possibilities, and implications . . . insofar as any non-AI developer can. I’ve begun experimenting with ChatGPT as a research tool (think of all the data it accesses), but it’s never going to be writing my blogs! Count on 100% Ellen, all the time.

Five years from now, when the next technological wonder launches, who knows what we’ll be saying?