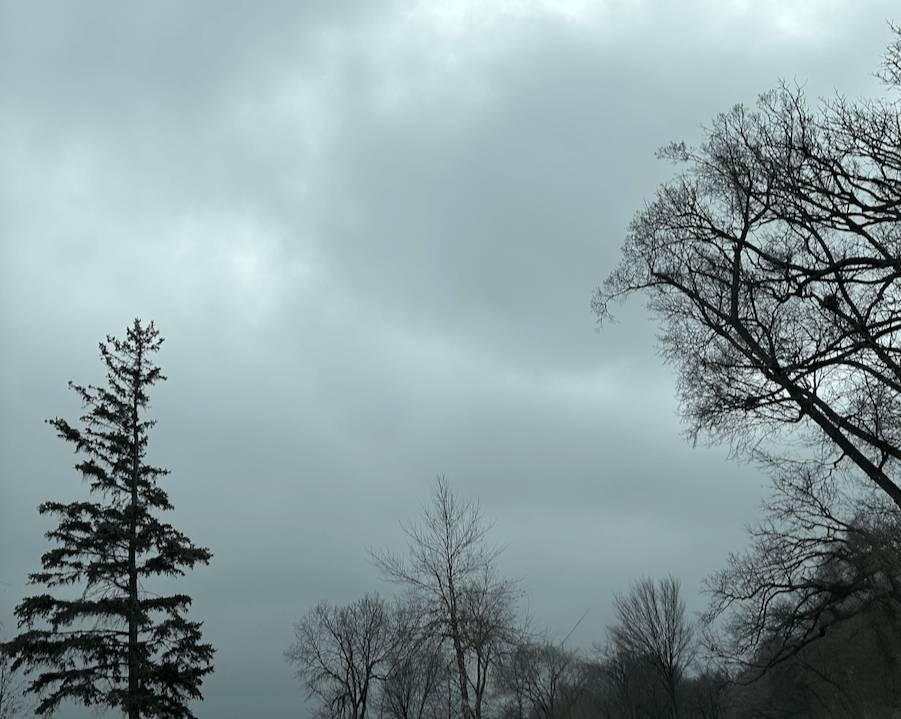

On days when November winds scour the streets and heavy gray clouds lean on the landscape, I feel Nature’s rhythms more deeply. Summer’s flowers have died and the natural world is dormant. I’m reminded that many of my elders are no longer with us. Even in my awareness of death and departures, I’m also comforted. These cycles are natural. This is how it’s meant to go.

Although I’m not a farmer, the idea of gathering the harvest resonates. Instead of crops, I gather my family. At Thanksgiving, we relish the ritual and continuity of turkey. My mother’s stuffing recipe. My husband’s mashed potatoes. My pecan pie. Foods we don’t crave any other time of year. Beyond the food served is a yearning to reaffirm our ties to family and tradition. This is what we do, have done for years (Even though our customary foods have evolved. Smoked turkey is tastier than roasted. None of us miss the yams.) We give thanks for what we have and who we have in our lives.

Nature’s rhythms are also woven into the circle of my extended family. Recently, we celebrated my mother-in-law’s 100th birthday. Four generations gathered in one place. There, too, we enjoyed the ritual of eating our favorite deep-dish pizza, fresh veggies, rich desserts. We honored her along with our connection as family. We reminded ourselves of who we are and who we come from.

For the first time, all three great granddaughters were able to attend. One of my granddaughters sat in my lap clapping with delight as the group sang “Happy Birthday.” Her newly met cousin danced and serenaded Gigi (her great grandmother) at the party’s end. Later the little girls played with abandon in the center of the living room surrounded by their grandparents and great aunts and uncles—just as my sons did 30 years ago.

Our circle is warm and loving. The cycle continues.