When my husband and I travel in the United Kingdom or Europe, we always visit some of the great cathedrals. That may seem odd, since neither of us is very religious. But cathedrals like St. Paul’s in London embody history, politics, and faith in a very visceral way and I’m very interested in history. The experience encompasses the best and worst of human nature.

The Shock and Awe of Churches

The architects and benefactors of great cathedrals intended to create a dramatic impact. And St. Paul’s does. The cathedral is an architectural marvel. The main aisle of cathedral goes on and on—while standing at one end of the church, I can see the other end, but just barely. The arched ceiling and dome soar high above the seats. Everywhere I look there are intricate decorations and many are covered with gold. I immediately feel small and insignificant in face of all the space and history, but that feeling gives way to a faint unease.

Sightseeing in a Place of Worship

Though I’m no longer a practicing Catholic, that upbringing is ingrained in me. It feels odd to see the whole gamut of tourists wandering around snapping photos (where permitted), peering at inscriptions on statues, ducking into alcoves, zigzagging across aisles in front of the pulpit and behind the altar, talking and pointing. There’s something distasteful about it, although obviously, I’m a tourist doing the same thing.

The premise of sightseeing in church is complicated. Many cathedrals charge admission and I assume the money helps maintain the building. Perhaps the religious authorities are also trying to give ordinary people access to a beautiful and potentially inspiring place.

Incredible Excess

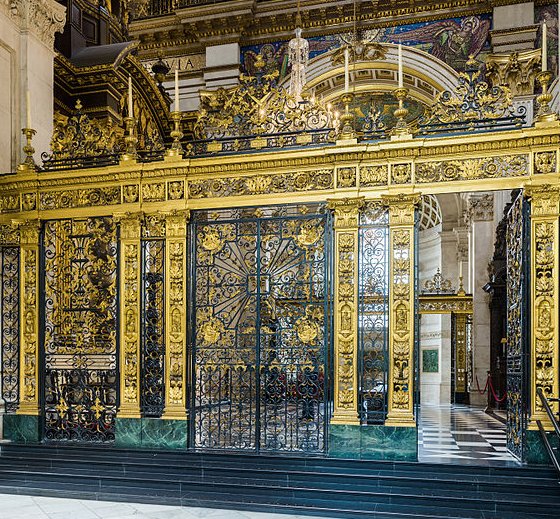

Cathedrals like St. Paul’s, the duomos in Florence and Siena, and St. Peter’s in Rome, all contain elaborate decorations—intricate mosaics, detailed wood and stone carvings, painted frescoes, golden candlesticks, chalices encrusted with jewels, lavishly embroidered altar cloths. The excess is fascinating but off-putting. I think about all of the money invested, perhaps for the glory of God but also as a demonstration of the power and wealth of the church, whether Anglican like St. Paul’s or Catholic like St. Peter’s in Rome. At first I am awed by the gilt and filigree, but then reminded of the greed, intolerance, and corruption that religious institutions have displayed historically.

Politics and Religion Are Intertwined in St. Paul’s

St. Paul’s was originally built as a Catholic church in 604. In 1087, it was demolished by fire. Rebuilding began in 1087 and the church was reconsecrated as a Catholic church in 1300. The Protestant Reformation, begun by Martin Luther in 1517, in response to the corruption in the Catholic Church, swept through Europe. In 1534, King Henry VIII split from the Catholic Church and established himself as head of the Church of England, so he could marry Anne Boleyn.

Politics and religion remained intertwined and turbulence continued in England until the 1660’s. During this period, St. Paul’s fell into disrepair and was used for a variety of things, including a marketplace. In 1666, King Charles II commissioned architect Christopher Wren to rebuild St. Paul’s, but the Great London fire destroyed the church and work was delayed until 1669. The church was completed in 1710. Now an Anglican church, the new St. Paul’s reflected the politics of the day.

In the dome is a mural with scenes from the life of St. Paul. It was painted in muted colors—a departure from the colorful decoration in Catholic churches. Statues and imagery of saints and angels is limited, in keeping with Protestant philosophy. Instead, statesmen like the Duke of Wellington and Admiral Lord Nelson are ensconced in huge lavish crypts. St. Paul’s remained a more somber looking place until the 1890’s, when Queen Victoria declared that it was dreary and uninspiring and asked to have mosaics installed.

The influence of politics is evident in the lavish decor, which speaks of wealth and power of the monarchs, the Church of England, and England itself. It’s also obvious in the inclusion of statues of political figures instead of religious figures.

I dislike the dichotomy and wish it could simply be an inspiring place of worship. But then I recall the way thousands of people flocked to St. Paul Cathedral at the end of World War II and realize that for many ordinary people, the cathedral is a spiritual place as well as a national symbol.

God in the Details?

Then I focus on the decorative details and think of the craftsmen who spent years setting tiny tiles to create the mosaics. Or the woodcarvers who labored and fussed over the leaves in the choir stall borders. Or the metalsmiths and artists who made the Tijou gates and the chalices. Hundreds of artisans throughout the church’s history worked to create something important and lasting. I want to believe that devoting years and years of their lives to the work was an expression of their faith. Thinking of the craftsmen restores my appreciation for the cathedral.